In the past twelve months, energy prices seem to have taken a life of their own. Their continued and, at times, shocking growth has raised concerns across the region and prompted differing responses and policy changes in each country. To get a more accurate picture of recent developments, we reached out to experts in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Moldova, Montenegro, Poland, and Turkey and asked them about the current energy prices, their impact on local economies, the drivers behind their growth, and whether any plans were in place to address the issue.

How High?

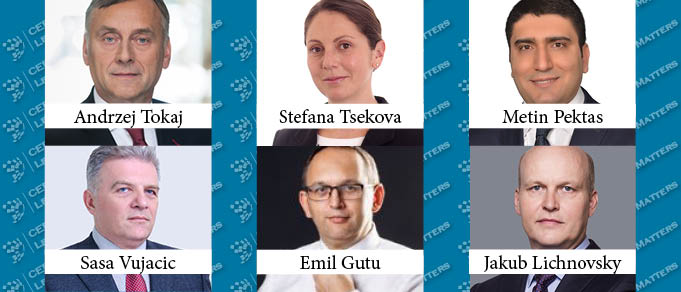

“Energy prices are high all over,” Schoenherr Partner Stefana Tsekova begins. “For Bulgaria, we’ve seen increases to record high levels for electricity prices. It was a really huge issue, with a deep impact on the country. The electricity prices have now settled, to some extent, but are still very high for the country’s standards,” she says. She reports that, according to market analysts, prices will probably hover around the EUR 200 per megawatt-hour point, for the rest of 2022.

“The Czech Republic has seen an overall increase in energy prices in the range of 30% to 50% in the public sector,” according to PRK Partners Partner Jakub Lichnovsky, “and by 300% and more for industrial entities, which depend on individual contracts with energy suppliers.”

Penteris Senior Partner Andrzej Tokaj says that in Poland, like elsewhere, “energy prices are on the increase, with this trend being particularly noticeable last year.” The price of energy has become a hot topic “in various political and social debates. Society is unhappy as energy prices for households have been hit hard and private purchases have decreased.”

It is the same in Turkey, according to Nazali Partner Metin Pektas, as “energy prices in the country are very much affected by global prices – we’re heavily impacted by importing raw materials for energy.”

In Montenegro, on the other hand, Vujacic Law Office Partner Sasa Vujacic reports that thanks to a standing decision by the government-backed by a resolution of the electricity company – electricity prices are fixed at EUR 98 per megawatt-hour. “It’s a state-imposed fixed price, the same for every consumer, and has been locked in since 2019.”

ACI Partners Competition Manager Emil Gutu says that electricity prices in Moldova are currently the one bright spot in the bleak larger picture of the country’s energy market. “It is only temporary, so let’s call it a short-term advantage. The country still has a long-term contract for electric energy supply, at fixed and relatively low prices, being entitled to buy electricity at USD 53.5 per megawatt-hour. Those prices are fixed until March 31, 2022.” He says that while electricity prices in Ukraine skyrocketed – the two countries’ power grids being completely interconnected, with energy flowing freely between them – for Moldova they’ve remained the same, for now. “The risk we face is that electricity prices will start to follow those of gas, as about 95% of the country’s power is produced by gas-burning thermal power plants.”

On the gas front, Moldova’s situation is dire, Gutu reports. “Prices have risen sharply for natural gas – our main energy source – having quadrupled, from about USD 150 per 1,000 cubic meters, a year ago, to almost USD 600 per 1,000 cubic meters in the past month or two. As a result, the regulated natural gas price for consumers has tripled, which was especially harsh during the winter.” He says the price hikes started in October 2021 and continued in January 2022.

Bulgaria’s situation is similar according to Tsekova. “The country is 99% dependent on imported natural gas, more than 90% of which is from Russia. With the ongoing political crisis, the price for Bulgaria also increased.”

“Most of our contracts for natural gas are with Russia,” Pektas notes as well. “In 2020 and 2021 the majority of those long-term contracts for the supply of gas expired and they had to be renegotiated. That was another issue which further affected the Turkish energy market,” he notes.

While Montenegro is studying multiple options, for gas coming in from Azerbaijan, Russia, Italy, or Tunisia, Vujacic says the country doesn’t import any gas right now, being somewhat insulated from the price shocks.

That is not the case for the Czech Republic, where Lichnovsky says the rapid increase in prices of gas and electricity caught the market off-guard. “The market has faced a collapse of traders and suppliers, many of which filed for bankruptcy. The biggest company to do so was Bohemia Energy, but there were many others too.” And prices were not the only reason for their collapse, he notes, citing the “poor risk management of the alternative suppliers, which resulted in the dramatic increase of energy prices for their clients, as they were forced to purchase electricity from the suppliers of last resort, for significantly higher prices”

While electricity and gas price outcomes differed from state to state, the situation of fuel prices seems to be the same across the board, with Tsekova, Gutu, and Vujacic reporting significant increases, along with global trends. For Bulgaria, fuel prices “are not regulated, so they do follow international oil prices closely. They are somewhat higher now, compared to six months ago, but they are within those international trends,” Tsekova says. In Moldova, “prices have increased by around 20 to 30% in the last six months. They have fluctuated a bit, but the price at the pump is now a quarter to a third higher – which is an added burden for both people and the economy,” Gutu reports.

“Montenegro imports diesel and gasoline from Croatia or Albania – as we don’t have the opportunity to bring them in through the port yet. And those prices have been incredibly high of late, the highest in ten years,” Vujacic says. “Numerous voices are complaining about the sizable fuel taxes as well but, even though the government announced it would shield consumers, no decision on fuel prices has been announced.”

Impact

In addition to inflation and rising interest rates in Poland, “growing energy prices have led to social concerns as individual consumers have less disposable income,” according to Tokaj. As for the economy in general, he notes “the growing demand for energy has led to a lack of competition among energy producers, and as a result, they have seen significant profit margin growth, in particular at the end of last year. Rising energy prices will cause the entire Polish economy to be less competitive for individual purchasers.” Even though any significant effect on the country’s economy is not yet noticeable, according to him, “it could become more visible in the long run.”

Vujacic reports that Montenegro has the benefit of being a net electricity exporter. “In the absence of large, heavy-industry consumers we’re able to export electricity, mostly to Italy, through an underwater cable. It’s a good position to be in, truly, but it was not reached by accident. While, by some accounts, Montenegro had created all the necessary documents for joining the single energy market, the government had the good sense to not go forward with that initiative.”

While Montenegro’s electricity prices are under control (and gas prices represent no issue), for many other commodities the situation in the country is the same as in the rest of Europe, according to Vujacic: “we import a lot of everything, and that comes in at international market prices, so inflation was felt in Montenegro as well.” The price of bread grew by around 15% according to him while for imported food products that increase reached as high as 70% to 75%. “As part of its social project Europe Now, our last government increased the minimum salary to EUR 450 (from the former EUR 250). That was a welcome change, of course, but taking into account the general increase of food and other prices, I’m not so sure those benefits were as far-reaching as was intended,” Vujacic adds.

“While we’ve not yet seen industrial players or Turkish producers filing for bankruptcy, all the energy and raw material price increases can be seen in the final end-consumer prices,” Pektas says. On top of that, the increased cost of energy became a significant problem for lower-income households in Turkey. “They can’t afford the new energy prices, as energy amounts to one-third or more of their income.” He notes that Turkish energy is subsidized, “through the public gas company and the power production company, and through tariffs. But by the middle of last year, the government had decided that the subsidies were not sustainable. So, they decreased the amount of the subsidies and the burden the state had to shoulder.” While end-user energy prices in Turkey are still lower than in many EU countries, Pektas stresses that purchasing power is also low and decreasing, “so the price increase impact on the public was quite harsh.”

Regulated energy prices came into play in Bulgaria as well, according to Tsekova. “We don’t yet have a fully liberalized market. We still have regulated prices in place for households and a moratorium on increasing the regulated prices for water and electricity valid until March 31, 2022. For now, they’ve been kept to a comparatively low level, set around mid-2021 prices.” But the system wasn’t perfect, she adds: “For example, university-owned student housing does not qualify as a household. So, students must pay the higher market-price bills and, in some cases, end up paying the same amount for a small room as they would pay for a three-bedroom apartment. Which shows just how steep the difference between regulated and unregulated prices has become.”

Bulgarian industrial consumers and legal entities pay market prices for energy, but the new government has made it a priority to support businesses, according to Tsekova. “They introduced some compensation measures, as state aid: those companies that qualify can receive a EUR 65 per megawatt compensation. While no end date for the program was announced yet, it will have to be stopped eventually, as Bulgaria can’t keep the market regulated this way for a long period.”

In an effort to combat price increases and the associated issues, the Czech government voided the 21% VAT which was attached to energy. “This was also an extreme method of combating inflation,” Lichnovsky reports. “Still, with the wider EU energy market not being properly calibrated, the Czech Republic cannot do much to save it, even with the abundance of energy sources our country has.” He adds that the price hike overflow, in terms of industry and agricultural products pricing, could be felt more significantly within the year. “Prices of crops could rise as the harvest comes – while this is a delay when compared to other price hikes, it is unavoidable.”

According to Gutu, the impact of those price increases in Moldova was both harsher and more widespread. “The Moldovan economy and citizens are particularly vulnerable to high energy prices because of several factors, the lower overall average living standards among them. This translates to energy poverty being widespread. It’s one thing for energy prices to double or triple when you have some amount of disposable income, but quite another when your disposable income was already close to zero. For many Moldovans, there’s just nowhere to cover the price difference from.”

On a brighter note, Tsekova reports that the higher prices have incentivized businesses to “start thinking about their energy transition and to consider investing in energy efficiency and renewables, as a means to combat price increases,” while new wind power investments have started to make economic sense again, “which is quite different to what was the case a year ago.”

The Why

Energy prices in the Czech Republic have recently gone up partly due to a combination of increasing natural gas prices and the low reserves of gas in European storage facilities, according to Lichnovsky. “The causes include geopolitics, cold weather, uncertainty over Nord Stream 2 [which, as of going to print, Germany has stopped its certification process], the decrease in wind power plants’ production, and increasing prices of emission allowances, so the rise of the price of electricity and gas is not solely a result of intra-market reasons,” he notes. The COVID-19 pandemic played also an important role. “The lockdowns have hit the market hard, making it difficult for a number of facilities to stay open. This led to the overall energy consumption on the market deteriorating and has caused troubles,” he adds.

He notes that, while “in the Czech Republic we have access to coal, lignite, gas, nuclear, and renewable sources of energy – and we have been successful in securing sufficient supply for ourselves, stabilizing the regional energy supply, and greatly contributing to avoiding blackouts in the entire region – we are on the CEE market for energy, thus the energy prices are more regional than country-linked.” And one big factor contributing to the rapid increase in prices of gas and electricity in recent months, Lichnovsky says, was that “Europe is highly – currently about 44% – dependent on gas imported from Russia through Gazprom, which is currently supplying gas only under long term contracts, has ceased its supply on the spot market and decreased its supply of gas to Europe by half while maintaining the prices.”

Further, Lichnovsky reports that lower electricity market liquidity also contributed to increased prices. “While it takes about CZK 0.30 to 0.50 to produce a kilowatt of electricity, the price for one is now between CZK 2.9 and CZK 9 – a six to ten times increase, or even more.” According to him, the EU model for trading electricity and gas had the aim to “weaken giant electricity producers, but it’s having negative externalities now.”

For Poland, the drivers behind the price increases essentially boil down to its mainly traditional ways of energy production, according to Tokaj. “The vast majority of energy comes from coal, not quite an environmentally-friendly energy source. The growing prices of the relevant carbon dioxide certificates are responsible for 20% of energy prices. At the same time, the transformation into using more environmentally-friendly energy sources is still in its infancy.” He also reports that “Poland imports coal from Ukraine, Russia, and even China and, as coal prices increase around the world, Poland also becomes vulnerable to such changes. In addition, the growing costs of production and the inefficiency of the existing power lines contribute to the energy price hikes.”

Pektas says that recent fluctuations in energy prices are pandemic-related, first of all. “We can chart the pandemic’s impact in two distinct periods. For most of 2020, the precautions were harsh, the supply chains were disrupted, and demand-oriented supply sharply declined. The lower demand decreased prices and, with both down, energy investments into infrastructure were suspended or stopped.” During the second period, in late 2020 and early 2021, he notes that “precautions relaxed and the trend reversed. The suppressed demand upsurged beyond normally expected growth and triggered above-normal supply increases. The previously stopped or suspended investments into energy infrastructure meant that suppliers couldn’t catch up. So, increased demand came with increased prices.” In addition, according to him, many developed countries applied monetary expansion policies, “further increasing energy demand as well as inflation – which again escalated energy prices, to levels which surprised all of us, recently.”

International developments also accelerated price growth. According to Pektas, “the tensions between Russia and Ukraine [at the time of the interview, not yet materialized] and the fact that most of the world’s LNG capacity was acquired by and shipped to China.” Finally, he highlights some Turkey-specific factors, like the serious exchange rate crisis. “The euro and the dollar doubled in Turkey. This meant that fuel prices more than doubled, as Turkey is not independent of global energy prices. Half of the country’s energy is produced by powerplants that use coal (more than 20%) and gas (25%) – so raw material prices and the exchange rate heavily impacted energy prices in Turkey, with the country having been hit harder than most,” Pektas concludes.

The causes for energy prices increasing in Moldova are no different from those in other European countries, according to Gutu. “Across Europe, it essentially boils down to a combination of unusually cold weather and market factors.” He says the country had difficulty mitigating the fourfold gas price increase by its eastern supplier, which translated as a price shock for consumers, through the tripling of the regulated natural gas price. He cites several reasons: “the country has no gas reserves, lacks significant renewable electricity generation capacities, its energy grid is actively interconnected only with Ukraine’s, comparatively energy-inefficient soviet-style urban housing is still widespread, and the economy is energy-intensive, with energy consumption per unit of GDP significantly higher than the EU-27 average.”

*** End of Part 1. Part 2, due to be published in Issue 9.3 of CEE Legal Matters will cover projections on the impact of the Russia – Ukraine war and what experts believe could alleviate the situation, if not return CEE markets to an energy pricing normal. ***

This article was written before the advent of the war in Ukraine and was originally published in Issue 9.2 of the CEE Legal Matters Magazine on March 1, 2022. More current articles on developments in Ukraine can be found in our #StandWithUkraine section. If you would like to receive a hard copy of the magazine, you can subscribe here.